“I wish I knew this sooner,” the Olympic coach said quietly, not into a microphone but almost to himself, after years of watching promising swimmers plateau. What followed was not a revolutionary gadget or secret workout, but a ruthless decision to erase one deeply ingrained, old-fashioned habit.

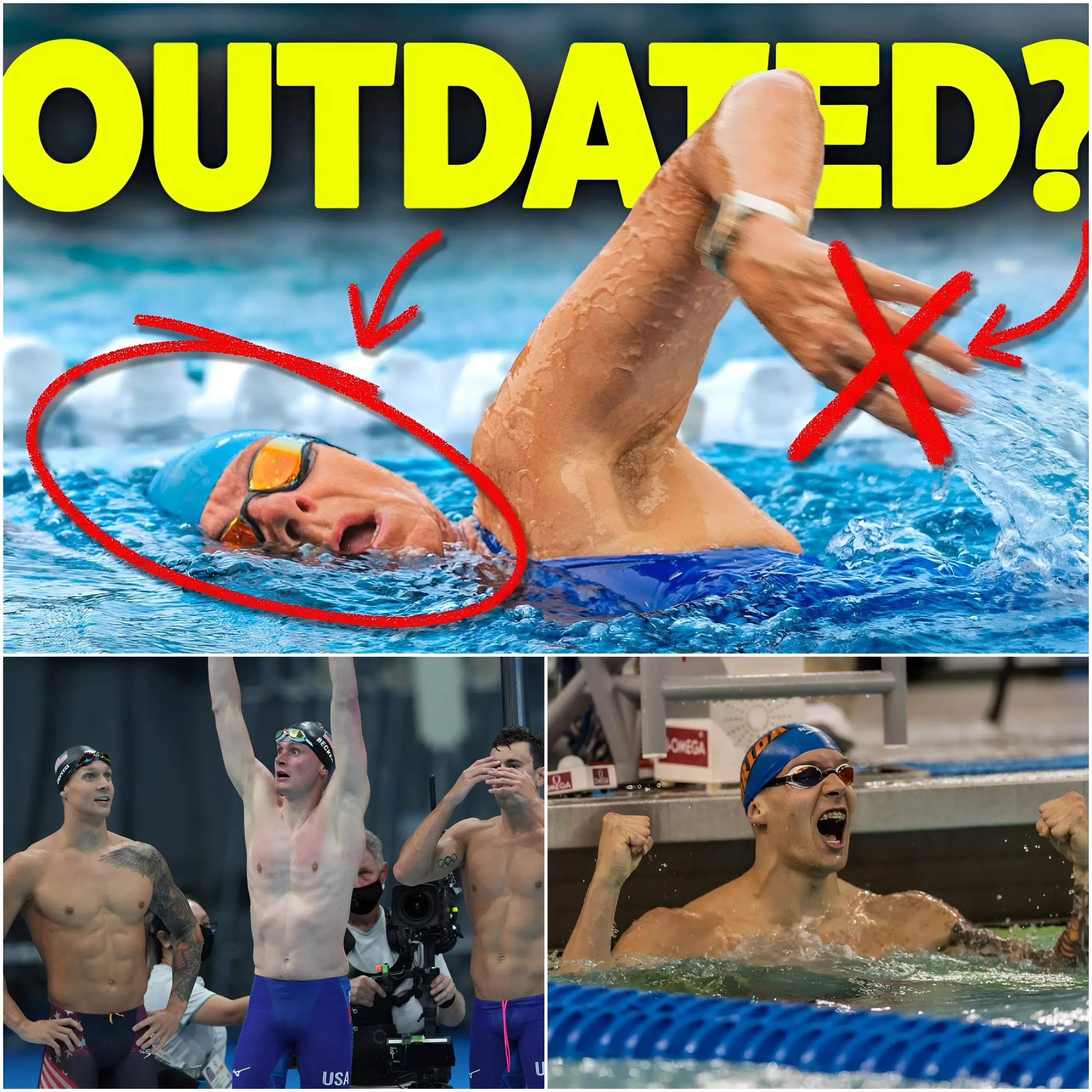

For decades, swimmers were taught that longer strokes automatically meant faster swimming. Coaches praised exaggerated reach, dramatic glide phases, and visible pauses that looked smooth to spectators. According to this coach, that visual elegance is exactly what has been silently stealing seconds from athletes, lap after lap.

The habit he now bans without negotiation is the prolonged front-end glide after each stroke. It feels controlled, efficient, and technically “clean,” but underwater data shows something else. Each micro-pause causes speed to drop sharply, forcing swimmers to re-accelerate again and again.

Re-acceleration is expensive. Water punishes hesitation more than land ever could. The coach explains that swimming is not about moments of perfection, but about relentless continuity. Once velocity drops, regaining it costs disproportionate energy, increasing fatigue while delivering no measurable advantage.

Many swimmers defend the glide because it feels powerful. The arms stretch, the body lengthens, and the mind believes distance per stroke equals efficiency. Yet race footage reveals a different truth: swimmers who appear smoother often lose ground against rivals maintaining constant propulsion.

At the elite level, races are rarely decided by strength alone. They are decided by how little speed you lose between movements. The abandoned technique creates tiny speed collapses that add up. Over a 100-meter race, those collapses can quietly cost half a second or more.

The coach describes it as “false efficiency.” On paper, fewer strokes seem better. In water, uninterrupted momentum is king. By eliminating the glide, his athletes increase stroke rate slightly, but more importantly, they preserve velocity from wall to wall.

This idea directly contradicts what many swimmers learned as children. Some were even punished for swimming “too fast” with shorter strokes. The psychological barrier is enormous. Letting go of the glide feels like chaos at first, like losing control of one’s technique.

Initial resistance was fierce. National-level athletes questioned whether the change would ruin their timing or spike heart rate too early. The coach insisted on trial periods, backed by timing systems and underwater cameras that left no room for subjective interpretation.

Within weeks, splits told the story. Athletes felt more tired in training, yet race-pace repeats became consistently faster. The water no longer dictated rhythm; the swimmer did. What felt harder was, paradoxically, more sustainable under competitive pressure.

The controversy deepened when younger swimmers adopted the method and began overtaking veterans during practice sets. Experience could not compensate for outdated mechanics. The pool hierarchy shifted, creating tension that the coach describes as unavoidable but necessary for progress.

Critics argue this approach sacrifices long-term endurance. The coach counters with physiology. Muscles prefer steady output over repeated spikes. Eliminating glide smooths the metabolic demand, reducing lactate surges caused by constant stop-and-go acceleration patterns.

Biomechanically, the argument is simple. Drag increases exponentially as speed drops and rises. Maintaining moderate, continuous speed is more efficient than alternating between fast pulls and dead moments. Water rewards consistency, not theatrics or textbook silhouettes.

This philosophy has already reshaped how the coach structures drills. There is less focus on exaggerated balance exercises and more emphasis on rhythm, timing, and seamless transitions between strokes. Athletes learn to feel propulsion rather than admire their own extension.

Parents watching practice sometimes complain that swimmers look “messy.” Arms cycle faster, strokes appear shorter, and the elegance once praised seems gone. The coach responds bluntly: medals are not awarded for looking graceful at half speed.

International competition has amplified the stakes. Swimmers from programs that abandoned the glide early are now setting the pace. Others scramble to adapt mid-career, fighting muscle memory formed over tens of thousands of laps.

The most unsettling revelation is how small the habit is. No radical retraining, no new strength phase, no equipment. Just the refusal to pause in front. That tiny moment of hesitation, repeated hundreds of times, becomes the invisible tax on performance.

The coach admits regret. He trained athletes for years before recognizing the damage of the glide. Some retired believing they lacked talent, never knowing technique held them back. That realization fuels his blunt honesty now, even when it angers colleagues.

Online forums erupted after snippets of his philosophy leaked. Traditionalists accused him of chasing trends. Supporters posted split comparisons and race footage. The debate exposed a deeper divide between swimming as an art form and swimming as applied physics.

What makes the discussion uncomfortable is its accessibility. Recreational swimmers, age-group athletes, and masters competitors can test this immediately. No permission required. Simply remove the pause, keep the hand moving, and observe how much smoother speed feels.

Not everyone will improve overnight. Timing errors can surface before coordination adapts. But the coach insists discomfort is part of progress. Water reveals truth quickly. The clock does not care how correct a stroke looks on land.

In the end, the message is not that old coaches were wrong, but that swimming evolved while habits froze. What once worked under different conditions now limits potential. Progress often begins not with adding something new, but with letting go of what feels familiar.