The history of French dynasties is impregnated with drama, power and tragedies that have left an indelible brand over time. From brutal executions to cruel destinations that seem taken from a nightmare, the deaths of some of the most emblematic characters in France not only shocked their contemporaries, but even today arouse curiosity and horror. Among the most shocking are the executions of “Hung, dragged and dismembered”, a method reserved for traitors, and others that exceed the imagination for their cruelty. Accompany us in this tour of the darkest episodes of the French monarchy, where guillotine, betrayal and suffering are intertwined in a story that you cannot stop reading.

The French Revolution (1789-1799) marked a turning point in the history of France, and with it came some of the most tragic deaths of royalty. Louis XVI, the last absolute king of France, was one of the first to face the edge of the guillotine. On January 21, 1793, in the Plaza de la Revolution (today Plaza de la Concordia), the monarch was executed after being declared guilty of high treason. According to the executioner Charles-Henri Sanson, Louis XVI maintained a stoic dignity: “People, I die innocent. I hope my blood can cement the good fortune of the French.” However, its execution was not a simple clean cut. The chronicler Louis Mercier describes how the guillotine blade, poorly tight, did not cross the neck of Louis XVI of a single pit, but cut part of his head and jaw, causing unnecessary suffering. This technical error, although brief, added a hue of horror to a moment already devastating.

María Antonieta, Queen Consort, followed an equally tragic destination. On October 16, 1793, the Austrian who had been vilified by the French people faced the guillotine. According to historian Antoine-Henri Berault-Bercastel, María Antonieta showed an admirable firmness: “She was taken to the scanning in a cart and did not denied her strength in that anguishing trance.” However, the chronicles of the time report how the people booed and spit while they were taken to the gallowing in a carriage without a capota. His appearance, marked by suffering, with white hair and demacrated body, contrasted with the image of the frivolous queen that the revolutionary propaganda had painted. His death not only symbolized the end of the monarchy, but unleashed a wave of violence known as the reign of terror, where thousands of lives, including those of nobles and commoners, were reaped.

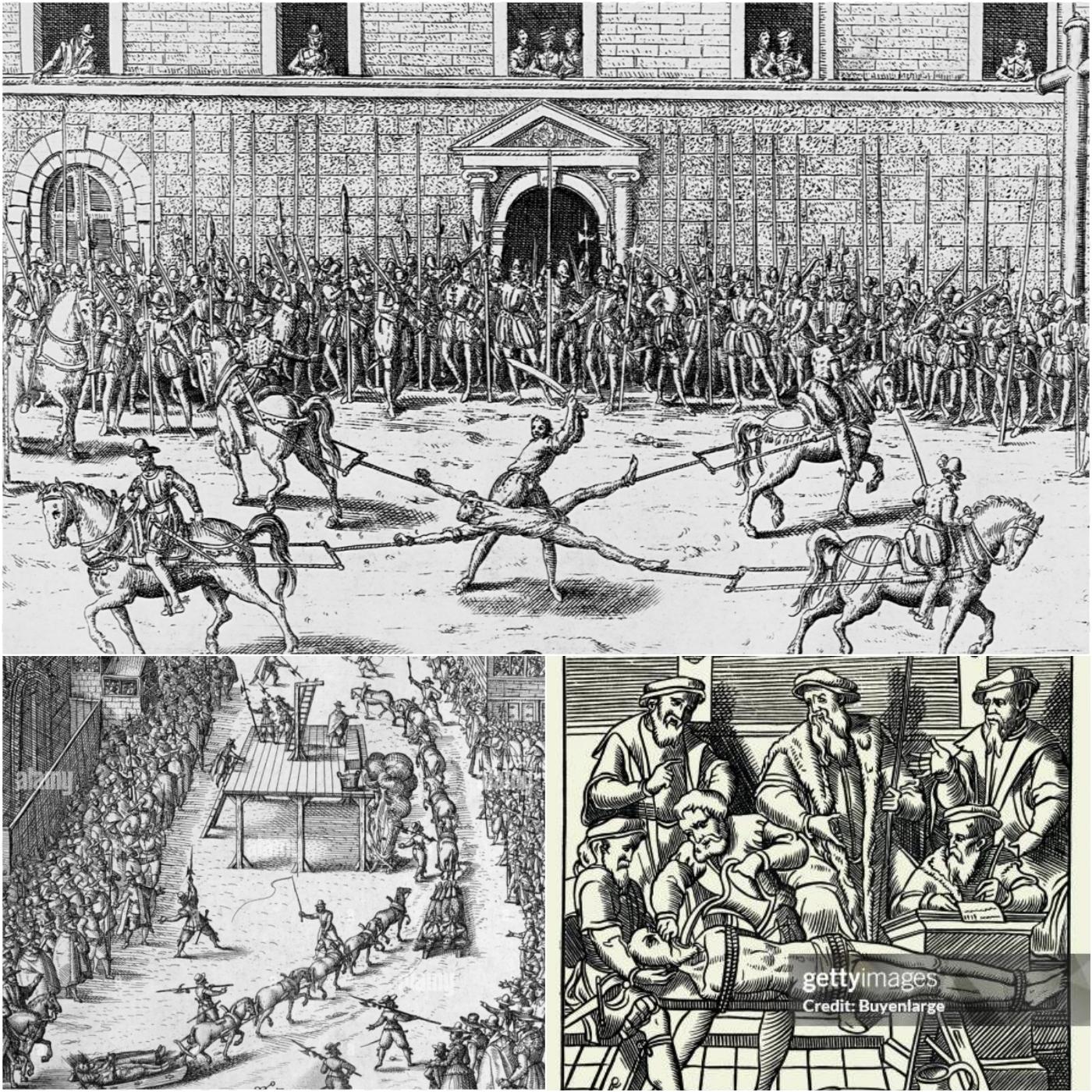

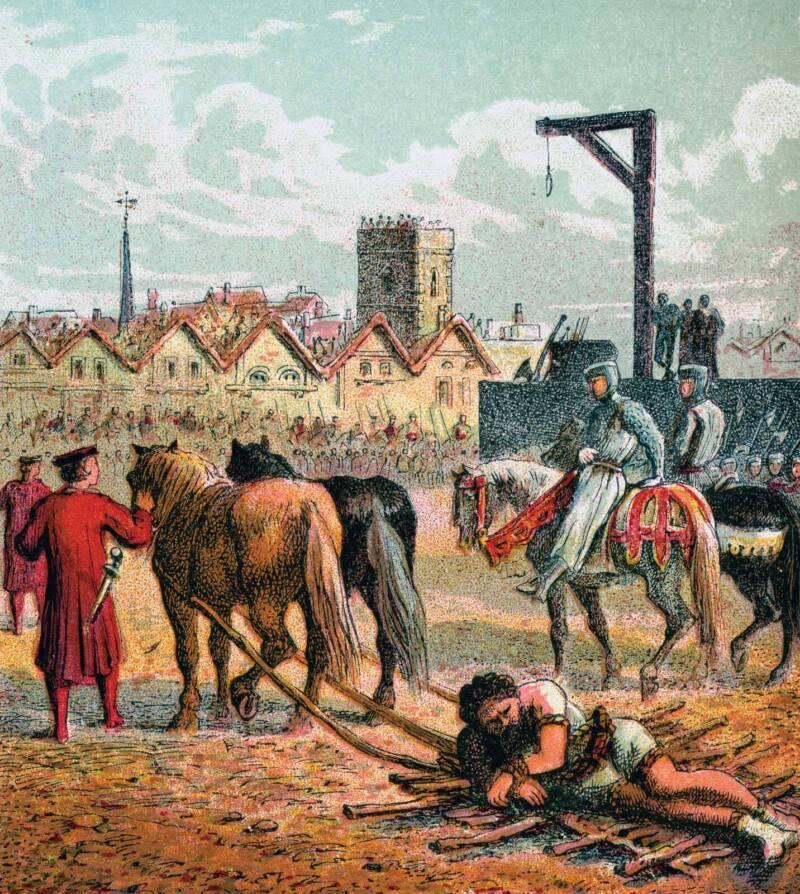

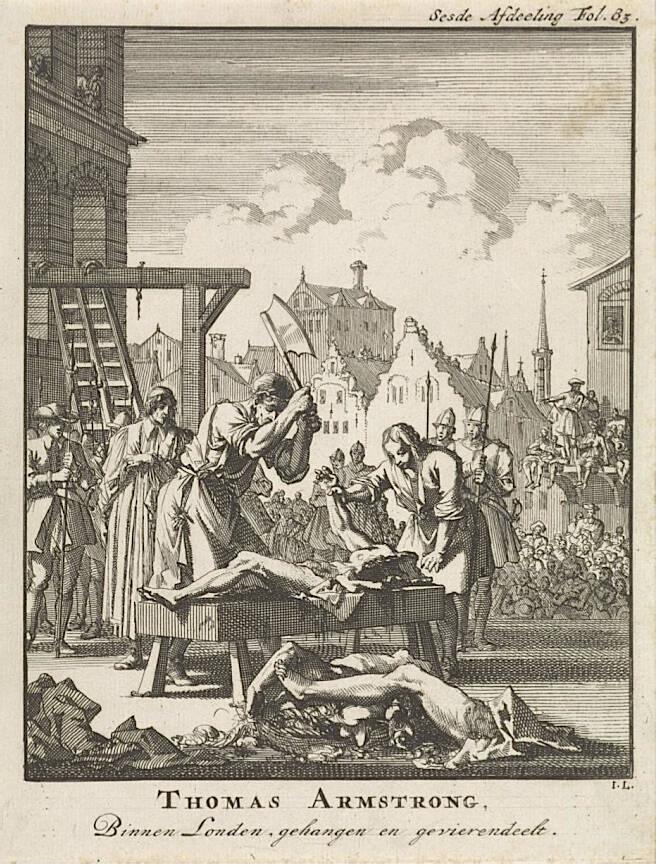

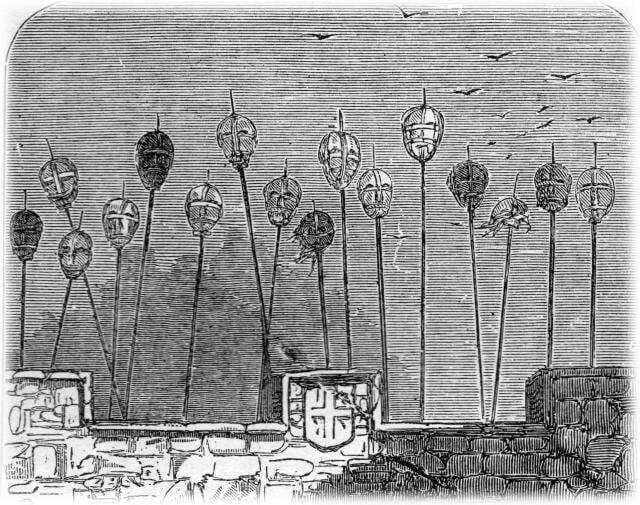

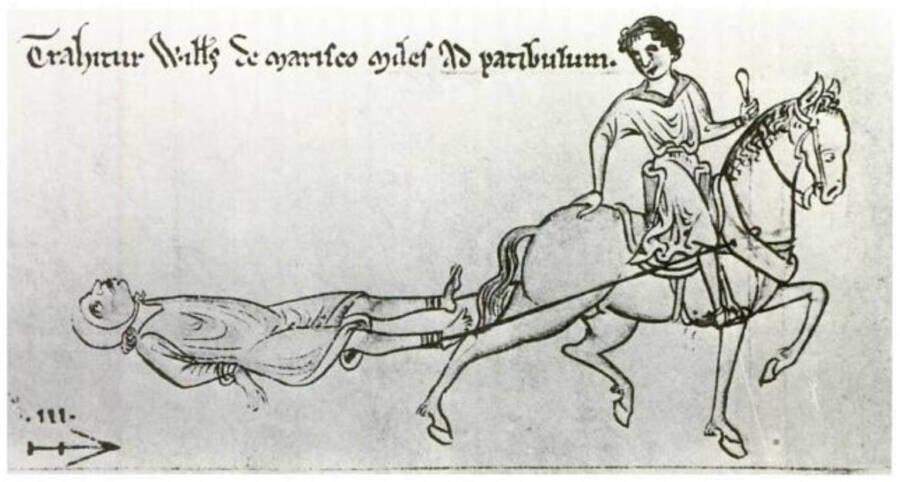

But the tragedies of the French dynasties are not limited to the revolution. Centuries before, during the Middle Ages, the punishments for betrayal were even more cruel. The “hung, dragged and dismembered” method was a sentence reserved for the most serious crimes, such as high betrayal. In England, this punishment was applied frequently, but in France there were also cases that shiver. For example, in 1314, the Brothers Felipe and Álción de Aunay were executed under this modality by their affair with the wives of the children of Felipe IV the beautiful. According to medieval chronicles, lovers were publicly tortured, castrated, hanging and finally dismembered, while the crowd watched with a mixture of fascination and repulsion. This episode, known as the scandal of the Tower of Nesle, marked a turning point in the capetos dynasty, weakening the real succession and feeding rumors of curses that would persecute the family.

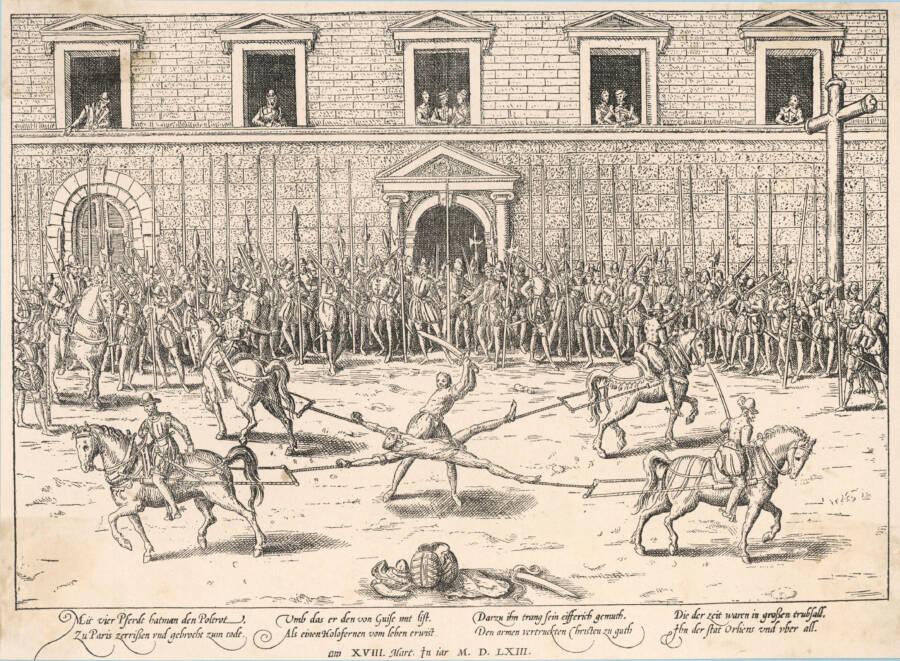

Another case that illustrates the brutality of executions in France is that of Robert-François Damiens, who in 1757 tried to kill Louis XV. Damiens underwent one of the most horrendous executions in French history. Tied to four horses, his body was literally torn apart in Grève’s Place before a crowd. The chronicler Nicolas Rétif of the Bretonne described the scene: “The people shouted, some with horror, others with a morbid curiosity, while the executioners struggled to complete the torture.” The execution of Damiens, thought of as a public warning, not only showed the cruelty of the old regime, but also sowed the seeds of discontent that would culminate in the revolution.

The Bourbon dynasty, which dominated France from the seventeenth century to the revolution, was not exempt from tragedies beyond public executions. Luis Carlos, the dolphin of France and son of Louis XVI and María Antonieta, died in circumstances that still feed the mystery. In jailed at 10 years during the revolution, Luis Carlos, known as Louis XVII, died in 1795 in the Temple prison. According to a guard quoted in the Halados del Evangelio magazine, the child, agonizing, spoke of listening to heavenly music: “Among all the voices, I have recognized my mother’s.” His death, probably due to tuberculosis and abuse, generated speculation about a possible escape, feeding the myth of the “lost king of France.” However, DNA analysis in 2000 confirmed that the heart preserved in the Basilica of Saint-Denis belonged to the young dolphin, closing an intrigue chapter that lasted two centuries.

These deaths, although marked by brutality, were not always limited to royalty. During the reign of terror (1793-1794), approximately 40,000 people, many of them plebeyas, lost their lives, according to historian Fernando Báez. The guillotine, nicknamed the “national blade”, became a symbol of equality in death, since it did not distinguish between noble and common. However, other execution methods, such as mass drowning in the Loira River or the Matanzas of September 1792, where 1,500 people died in a few days, reflect the ferocity of the time. The historian Jean-Clément Martin points out that “the word‘ execution ’evokes a deliberate destruction, beyond simple death”, highlighting how the revolution transformed violence into a public show.

Why do these stories continue to fascinate? Perhaps because they reveal the fragility of power and the rawness of justice in times of crisis. The French dynasties, from the capetos to the Bourbons, not only ruled with splendor, but also faced destinations that seem taken from a Shakespearian tragedy. The execution of Louis XVI marked the end of an millennium of absolute monarchy, while the death of María Antonieta became a cultural icon, immortalized in art and literature. Even medieval punishments, such as Aunay’s brothers, remind us that power has always had a price, and often, that price was paid with blood.

Today, when looking back, these tragedies invite us to reflect on the nature of power and justice. Guillotine, which promised a quick and “humanitarian” death, and brutal methods such as dismembered, show us a past where violence was both a punishment and a message. The voices of Louis XVI, María Antonieta and the young Luis Carlos resonate as echoes of a France who, in his struggle for freedom, was sometimes lost in the dark of his own ideals. What other stories of French dynasties remain hidden, hoping to be rediscovered? His legacy, as tragic as fascinating, is still alive in our collective imagination.