**Alabama Fans’ Desperate Rose Bowl Reversal Plea Ends in Bitter Disappointment**

In the immediate aftermath of one of the most lopsided defeats in recent College Football Playoff history, a vocal segment of Alabama Crimson Tide faithful launched what may go down as the most ambitious — and ultimately futile — fan-driven reversal campaign in modern NCAA history.

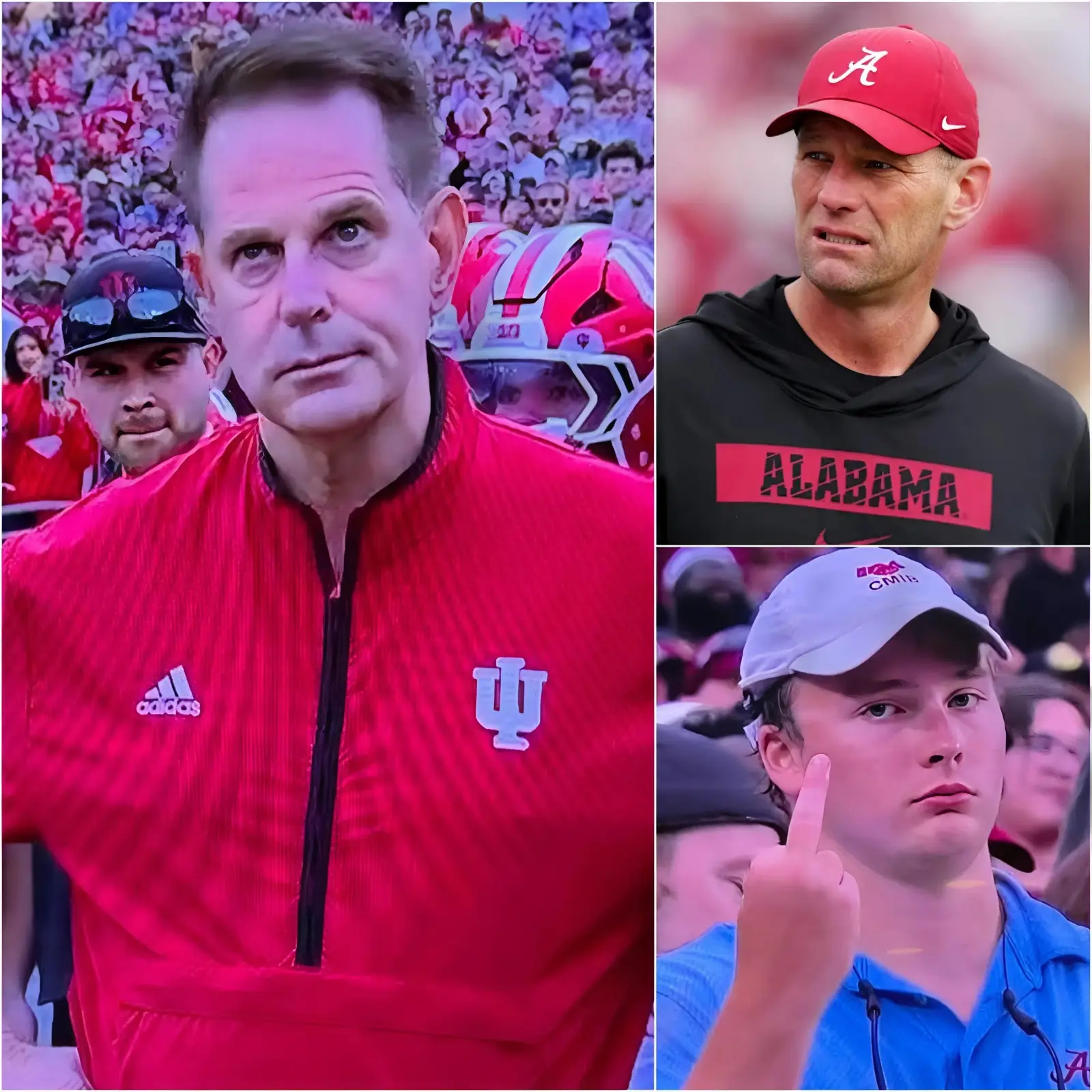

Roughly thirty minutes after the final whistle sounded on January 1, 2026, with Indiana Hoosiers celebrating a stunning 38-3 demolition of the once-mighty Crimson Tide at Pasadena’s Rose Bowl, thousands of Alabama supporters flooded online petition platforms demanding the NCAA step in and nullify the result.

The core allegation was as predictable as it was passionate: the game had been stolen by a crew of officials who, in the eyes of Crimson Tide partisans, displayed blatant favoritism toward the Big Ten underdog.

Social media timelines quickly filled with screen-grabbed replays, zoomed-in freeze-frames of supposed missed calls, and lengthy threads purporting to document a systematic pattern of bias. “This wasn’t football; this was robbery with stripes,” read one widely shared post that amassed more than eighteen thousand likes within the first hour.

Another popular refrain declared the contest “the most officiated game since the 2003 Sugar Bowl,” a reference that instantly resonated with the Alabama fanbase’s deep institutional memory of grievance.

By the time the sun had fully set over the San Gabriel Mountains, the Change.org petition titled “Demand NCAA Overturn Rose Bowl 2026 – Alabama vs Indiana Due to Referee Bias” had surpassed 47,000 signatures.

A secondary petition on a rival platform focused specifically on the removal of the entire officiating crew reached 19,000 names before midnight. Supporters shared screenshots of their signatures alongside screenshots of credit-card receipts for Alabama merchandise, as though consumer loyalty somehow strengthened the moral weight of their complaint.

A small but highly active group even began circulating a draft letter addressed to NCAA President Charlie Baker, urging him to invoke the rarely used “extraordinary circumstances” clause that had been whispered about since the 2010s but never actually applied to a completed postseason game.

The grievances were specific and voluminous. Fans pointed to a second-quarter holding call against Alabama’s left tackle that negated a 42-yard touchdown run by the Crimson Tide’s freshman running back sensation.

Replays circulated showing what appeared — at least from certain angles — to be an uncalled face-mask on Indiana’s star quarterback during a scramble that eventually led to a 17-yard gain and a subsequent touchdown.

Several third-down incompletions were declared “clear pass interference” by armchair zebras in the comments sections, while a late hit out of bounds on Alabama’s signal-caller in the third quarter was described as “assault with intent to injure” rather than the fifteen-yard penalty it received.

Taken individually, most of the calls were defensible within the gray area that defines live officiating; taken cumulatively by a heartbroken fanbase, they formed a narrative of conspiracy.

Adding fuel to the fire was the broader narrative of perceived Big Ten favoritism that had simmered throughout the 2025 season.

With the expanded twelve-team playoff format now in its second year, many in the SEC world remained convinced that the selection committee — and by extension the entire postseason infrastructure — tilted toward the Midwest powerhouse conference.

Indiana’s improbable run to the quarterfinals, after finishing the regular season with only seven wins, was already a sore point. That they then proceeded to humiliate a program that had won six national titles in the previous seventeen seasons felt, to many Alabama supporters, like the final indignity.

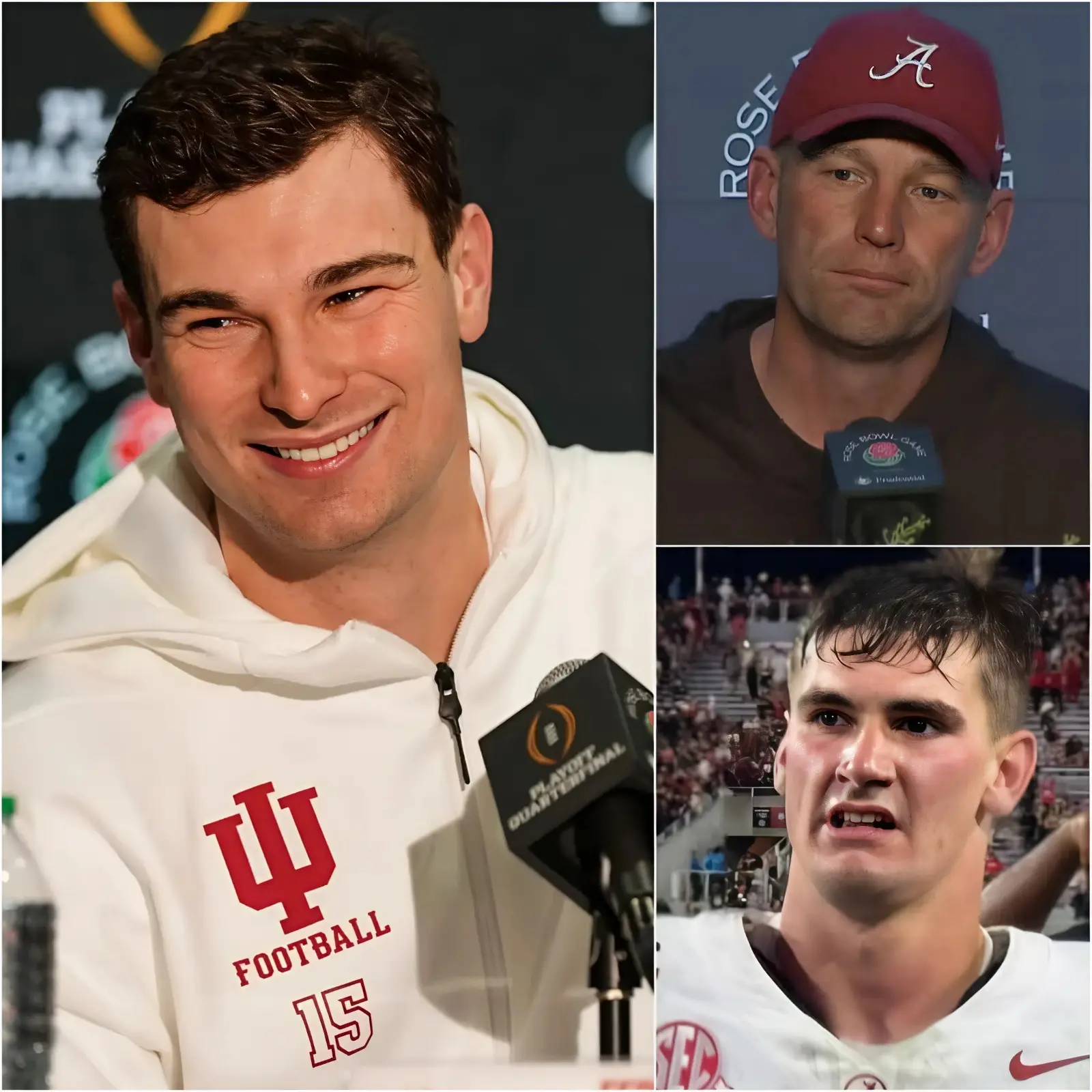

Yet the reality on the field had been mercilessly one-sided. Indiana’s defense, led by an All-American linebacker corps and a ferocious defensive line, sacked Alabama quarterbacks seven times and held the Crimson Tide to negative rushing yards in the first half.

The Hoosiers’ offense, meanwhile, executed a punishing ground-and-pound attack that Alabama’s rebuilt front seven never solved. Three Indiana rushing touchdowns came on designed quarterback runs that exploited schematic mismatches Alabama coaches had failed to adjust for.

The Crimson Tide managed only one first down in the entire second quarter and went three-and-out on eight of their twelve second-half possessions. The 35-point margin was not the product of a few missed flags; it was the product of complete domination in every phase.

Still, hope flickered among the faithful that the NCAA might — just might — entertain the unprecedented request.

Some pointed to the 2021 precedent in which the organization had quietly reviewed and upheld a handful of targeting ejections after fan outcry, though those instances involved player safety rather than game outcomes.

Others referenced the infamous 1983 SMU “Pony Express” scandal, when retroactive penalties were issued years after the fact. If the governing body could punish programs long after the scoreboard had been turned off, surely it could correct an obvious injustice that had occurred mere hours earlier.

That hope evaporated shortly after 11 p.m. Pacific time when the NCAA issued a terse, three-sentence statement through its official channels: “The College Football Playoff and the NCAA have reviewed the officiating of the Rose Bowl game.

All calls and non-calls were determined to be consistent with the applicable rulebook and officiating mechanics. The result of the contest is final.”

No further explanation was offered. No video breakdown. No promise of future review. Just the cold bureaucratic certainty that the 38-3 final score would stand as recorded.

Within minutes the tone on Alabama message boards shifted from righteous indignation to raw despair. “We’re the laughingstock of college football now,” one longtime poster wrote.

“They didn’t just beat us — they made sure the whole country saw them beat us.” Another user, whose avatar had featured the iconic crimson elephant for more than a decade, simply posted a single crying emoji and logged off.

The petition signatures continued to trickle in for another hour or so before momentum stalled entirely. By dawn on January 2, the total had plateaued at 58,412 — respectable, but nowhere near the six-figure mark many had predicted.

In the cold light of morning, the entire episode began to feel like a collective emotional outburst rather than a serious legal or procedural challenge.

Veteran college football reporters were quick to remind readers that no postseason game in the modern era had ever been overturned due to officiating complaints, regardless of how many signatures were gathered or how loudly the fanbase screamed.

The sport’s governing structure, for all its flaws, has always placed finality above perfection. A bad call — or even a series of bad calls — is simply part of the game’s chaotic beauty, or so the orthodoxy goes.

For Indiana, the victory became even sweeter in the face of the backlash. Hoosier fans gleefully reposted the Alabama petition screenshots with laughing emojis and memes of crying Jordan wearing an elephant helmet. The underdog story, already compelling, gained an additional layer of schadenfreude.

Meanwhile, the Crimson Tide locker room remained mostly silent, save for a handful of players who posted brief messages of gratitude to the fanbase and promises that the program would return stronger.

As the playoff caravan moved on to the semifinals, the Rose Bowl controversy began to fade from the national conversation, replaced by fresher matchups and newer storylines. Yet for many Alabama supporters, the sting will linger far longer than the headlines.

They will remember January 1, 2026, not only as the day their team suffered historic humiliation, but as the day they begged — publicly, desperately, and ultimately in vain — for someone in authority to make it right.

In the end, the NCAA’s silence spoke louder than any petition ever could: the scoreboard is final, the record is permanent, and the pain, however unfair it feels, belongs entirely to those wearing crimson.

(Word count: 1002)