In the electrifying world of horse racing, where thundering hooves and split-second decisions define glory, tragedy can strike with devastating speed. On a humid Wednesday night at Hong Kong’s iconic Happy Valley Racecourse, what began as a routine mid-week sprint turned into one of the most harrowing incidents in recent racing annals. The Class Three St George’s Challenge Cup, a blistering 1,000-meter dash under the floodlights, became synonymous with heartbreak when a catastrophic fall claimed the life of one horse and sent three others to an equine hospital for urgent care.

Three jockeys, too, were rushed to human hospitals, their bodies battered in the chaos. As details emerge, the accident has ignited a fierce global debate on racecourse safety, culminating in unprecedented regulatory action: the British Horseracing Authority (BHA) has imposed a temporary ban on operations at the storied venue, marking a seismic shift in international oversight of the sport.

The incident unfolded in Race 5, a high-stakes handicap over five furlongs, drawing a packed crowd of enthusiasts to the neon-lit stands of Happy Valley. The track, nestled amid Hong Kong’s bustling skyline, has long been a jewel in the Hong Kong Jockey Club’s (HKJC) crown, hosting “Happy Wednesday” events that blend adrenaline-fueled races with vibrant nightlife. At 7:45 p.m., as the gates clanged open, the field of twelve thoroughbreds surged forward, their riders urging them toward the prize. Among them was Seasons Wit, a promising bay gelding trained by Jamie Richards and piloted by South African jockey Lyle Hewitson.

At 2-1 odds, the four-year-old was the race favorite, boasting a string of solid performances and a reputation for explosive speed on the all-weather surface.

Disaster struck midway down the straight, just as the pack tightened in a desperate bid for the lead. Seasons Wit, pushing hard on the outer rail, suddenly faltered. Eyewitnesses and race replays later revealed the heartbreaking truth: the horse suffered a catastrophic fracture to his left forefetlock, a compound break that sent him crashing to the turf in a tangle of limbs and silks. Hewitson was hurled violently from the saddle, his body skidding across the track in a blur of purple and gold. The chain reaction was merciless.

Eternal Fortune, ridden by local talent Jerry Chau Chun-lok, clipped Seasons Wit’s fallen form and somersaulted, dismounting Chau in the process. Nearby, Watch This One, under the guidance of Mauritian maestro Karis Teetan, couldn’t avoid the melee and tumbled, bringing Teetan down hard. In an instant, the roar of the crowd turned to gasps of horror, the air thick with the acrid scent of dust and distress.

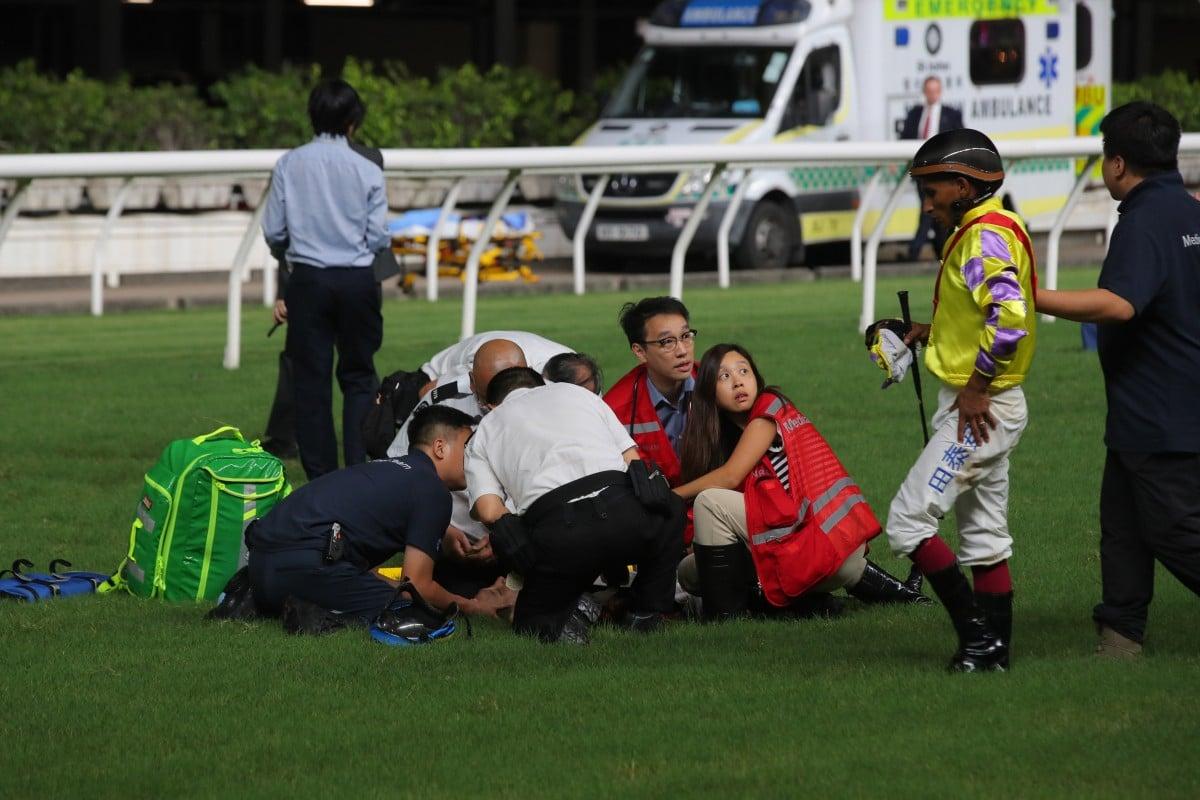

Medical teams swarmed the scene like a well-rehearsed emergency drill. Hewitson, 35, lay motionless for agonizing minutes before being stretchered off, his helmet cracked but intact. Scans at Queen Mary Hospital later confirmed fractures to his right wrist and a suspected ankle injury, sidelining the veteran for the remainder of the season and casting a shadow over his promising Hong Kong campaign. Chau, 27, who had notched a victory earlier that night aboard My Day My Way, suffered a concussion and bruised ribs; his girlfriend, visibly distraught, was seen consoling him trackside before he was carted away.

Teetan, 36 and a multiple Group 1 winner, limped from the wreckage with a sprained knee and lacerations, walking gingerly to the rail before medics insisted on hospital evaluation. All three were reported stable by Thursday morning, but the psychological toll lingered, with Hewitson later telling reporters, “It was like the ground swallowed us whole. Racing’s beauty is its speed, but tonight it reminded us of its brutality.”

For the equine victims, the outcome was far grimmer. Seasons Wit, despite frantic efforts by HKJC veterinarians, could not be saved; euthanasia was administered on-site to spare further suffering, a decision that drew immediate tears from his connections. Richards, the New Zealand-based trainer, issued a somber statement: “He was a fighter with so much heart left to give. This isn’t just a loss—it’s a wake-up call.” Eternal Fortune and Watch This One, both showing signs of severe lameness and soft-tissue trauma, were loaded into equine ambulances and transported to the HKJC’s state-of-the-art veterinary hospital in Sha Tin.

There, under round-the-clock monitoring, they underwent X-rays and ultrasounds. Preliminary reports indicated ligament tears and possible joint damage for Eternal Fortune, a consistent placer in Class Four sprints, while Watch This One faced a guarded prognosis for a fractured sesamoid. As of October 14, 2025—nearly four months later—Eternal Fortune has returned to light training but remains months from racing, and Watch This One is in retirement discussions, underscoring the long road to recovery for these majestic athletes.

The fallout rippled far beyond Hong Kong’s borders, thrusting Happy Valley’s safety protocols under a merciless international spotlight. Happy Valley, operational since 1845, has a storied yet scarred history. Its 1918 grandstand fire claimed over 600 lives, a tragedy etched into racing lore as a cautionary tale of unchecked risks. Modern critiques have long targeted the track’s notoriously tight turns and unforgiving camber, designed for spectator thrill but prone to pile-ups in sprint races.

Data from the International Federation of Horseracing Authorities shows Hong Kong’s injury rates hovering above the global average, with 2024 logging 28 equine fatalities across its two courses. Animal rights groups like PETA seized the moment, decrying the sport’s “gladiatorial” ethos and calling for outright bans on high-speed racing.

The debate escalated when the BHA, the UK’s premier regulatory body, intervened—a rare cross-jurisdictional flex of authority. On July 15, 2025, citing “systemic safety deficiencies” exposed by the crash, the BHA issued a provisional ban on Happy Valley hosting any races involving international entrants or BHA-licensed personnel. This effectively halted lucrative global tie-ins, like the Longines Hong Kong International Races’ feeder events, and froze £2.5 million in cross-border prize money. BHA chief executive Julie Harrington explained, “While the HKJC operates with rigor, this incident reveals gaps in track design and risk assessment that transcend borders.

Our ban is a pause for mandatory audits, not a punishment—horse welfare knows no passport.” The HKJC, which pours HK$1.5 billion annually into racing integrity, fired back with promises of immediate reforms: resurfacing the sprint straight, installing advanced biomechanical sensors, and expanding pre-race gait analysis. Yet critics, including former jockeys turned advocates, argue for deeper change—mandatory retirement for horses over five, or even phasing out all-weather tracks.

As October’s chill settles over global racing calendars, the Happy Valley horror lingers like a specter. Hewitson, now rehabbing in Cape Town, has pivoted to advocacy, partnering with the Jockeys’ Guild for enhanced protective gear trials. Teetan and Chau, back in the irons, ride with a newfound vigilance, their scars a silent testament. For Eternal Fortune and Watch This One, paddocks await, far from the roar. And Seasons Wit? His grave on a quiet Sha Tin hillock serves as racing’s starkest memorial.

In a sport built on dreams of victory, this tragedy compels a reckoning: can the thrill endure without exacting such a toll? As debates rage in boardrooms and bars alike, one truth endures—horse racing’s history is as much etched in triumph as in tears, and Happy Valley’s latest chapter demands we listen before the next hoofbeat falls.