DENVER, Colo. – In the aftermath of one of the most heartbreaking playoff eliminations in recent Buffalo Bills history, left tackle Dion Dawkins turned to social media to vent his fury. What he posted wasn’t just a highlight reel—it was a direct accusation that lit the fuse on an explosive league-wide controversy.

The Bills’ season ended in brutal fashion on January 17, 2026: a 33-30 overtime loss to the Denver Broncos in the AFC Divisional Round at Empower Field at Mile High. The game had already been marred by controversial officiating, including two late pass-interference calls that handed Denver prime field-goal position. But the flashpoint came on a third-and-11 play late in overtime, when quarterback Josh Allen launched a deep ball to receiver Brandin Cooks.

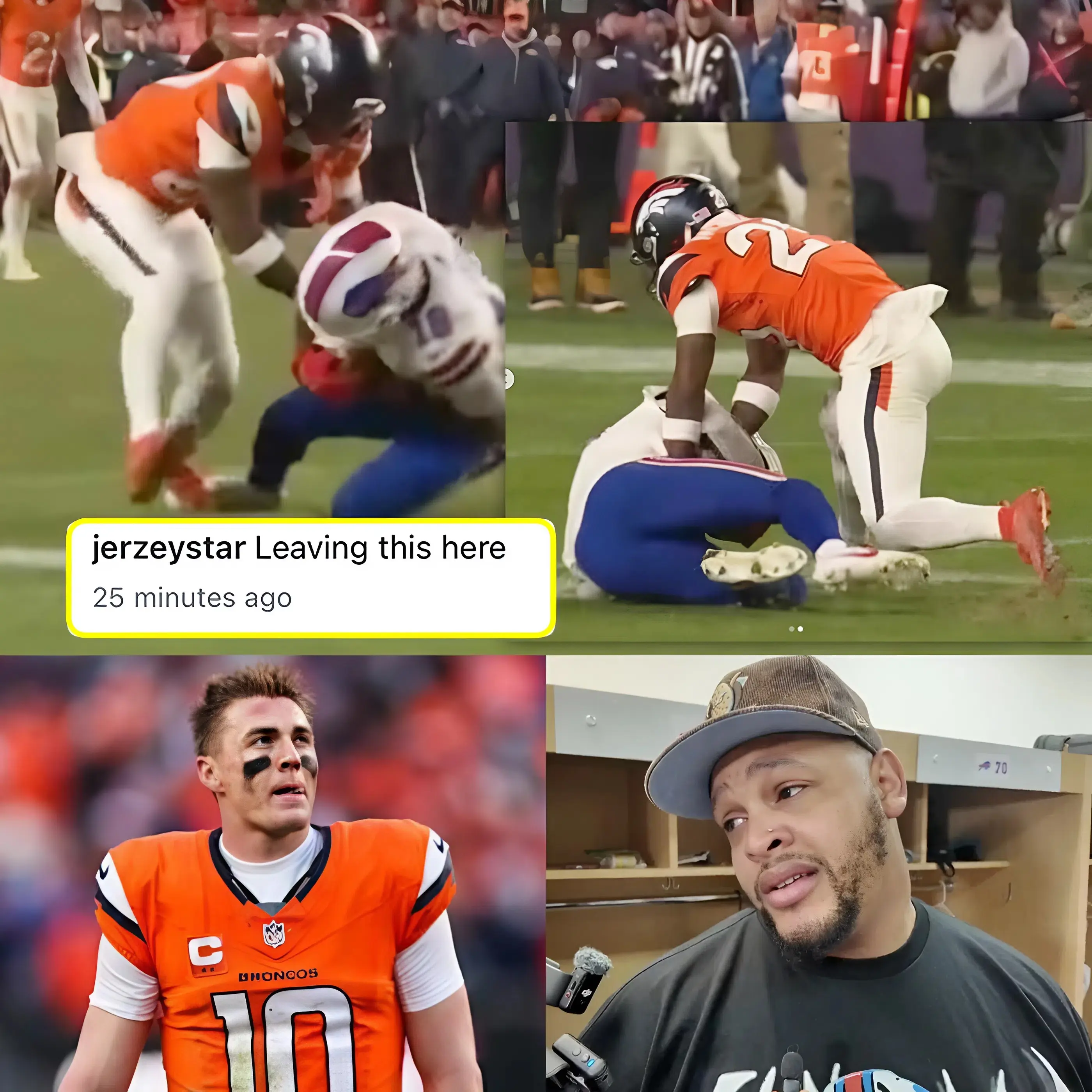

On the field, the play unfolded in a blur. Cooks soared high, secured the ball against his chest as he descended, took several steps, and appeared to be driven to the turf by Broncos cornerback Ja’Quan McMillian. The officials immediately signaled interception, with McMillian emerging from the pile holding the football. No challenge was allowed; the call stood. Denver took possession, milked the clock, and booted a chip-shot field goal to end Buffalo’s campaign.

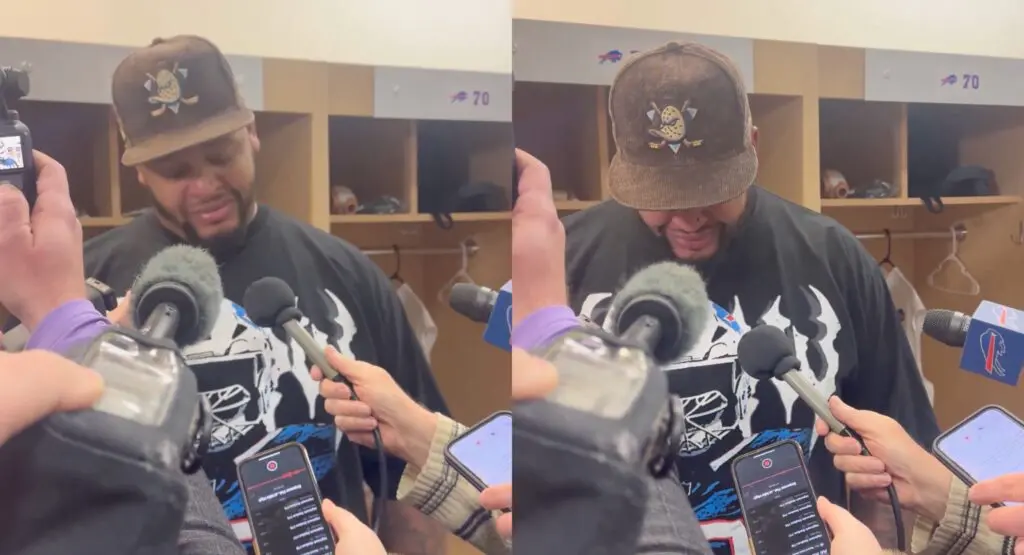

Dawkins, the Bills’ longtime Pro Bowl left tackle and one of Josh Allen’s fiercest protectors, refused to let the moment die quietly.

Within hours of the final whistle—still in the dead of night on January 18—he uploaded a series of zoomed-in, annotated screenshots straight from the broadcast replay. The images showed Cooks’ hands clearly underneath the ball, his feet establishing position before contact, and McMillian’s right arm snaking in to rip at the football in a violent, twisting motion. Dawkins captioned the post with three simple, searing words:

“Dirty rip. Period.”

The implication was unmistakable: McMillian hadn’t merely stripped the ball in a clean football play—he had committed what Dawkins believed was a deliberate, rules-violating yank that should have been flagged as unnecessary roughness or, at minimum, prompted an instant review for simultaneous possession or a completed catch.

The internet exploded. Bills Mafia flooded Dawkins’ mentions with fire emojis and calls for justice. Broncos fans fired back, accusing the tackle of sour grapes. National analysts dissected the images frame-by-frame on overnight shows. By sunrise, the NFL’s officiating department had no choice but to respond.

In an extraordinary Sunday morning statement, the league announced it had launched an immediate post-game review of the play. The conclusion, released in a terse but pointed memo, left little room for interpretation—and forced everyone to re-watch the sequence on repeat.

“Upon thorough examination of all available angles,” the statement read, “the ruling of interception on the field is confirmed as correct under current catch-and-possession guidelines. However, the physical action by the defender in dislodging the ball after the receiver had clearly established control and begun his football move constitutes a violation of Rule 12, Section 2, Article 8 (Unnecessary Roughness – Horse-Collar, Rip, or Twist). This should have resulted in a 15-yard penalty and an automatic first down for the offense.”

The NFL stopped short of overturning the game result—playoff contests are final once concluded—but the admission was damning. For the first time in recent memory, the league publicly acknowledged a missed call that directly altered the outcome of a postseason elimination game.

McMillian’s technique—described by former officials as a “classic rip-and-tear”—has long existed in a gray area. Defenders are allowed to punch at the ball, but the moment control is established and the receiver begins to transition into a runner, ripping becomes illegal. The league’s memo included a rare breakdown: three still frames showing Cooks’ possession, the moment of ground contact, and McMillian’s arm wrenching upward in a twisting motion that many analysts called “borderline dangerous.”

Dawkins’ post, which garnered over 1.2 million views in its first 12 hours, became the catalyst. Teammates quietly rallied behind him. Brandin Cooks, who had been diplomatic in his immediate postgame comments (“I’ve got to secure it better”), liked the post within minutes. Even Josh Allen, who had spent much of the night in tears accepting blame for the loss, reposted Dawkins’ images with a single emoji: a clenched fist.

The fallout spread quickly. Bills head coach Sean McDermott, already furious about the no-review interception call, used his Monday press conference to hammer the point home.

“We preach toughness, we preach physicality—but there’s a line,” McDermott said. “When a play ends a season because that line is crossed and no flag flies, that’s a problem bigger than one game.”

Broncos coach Sean Payton pushed back, calling the league’s statement “Monday morning quarterbacking at its finest” and defending McMillian as a player who “plays the game the right way—hard and clean.”

But the damage was done. Social media timelines filled with side-by-side comparisons of the McMillian rip and similar penalties called earlier in the season. Former players, including Hall of Famer Terrell Owens and analyst Richard Sherman, weighed in, with Sherman calling it “the dirtiest non-call I’ve seen since the Tuck Rule era.”

For Bills fans, already reeling from another playoff heartbreak, Dawkins’ post and the NFL’s rare concession became a bittersweet form of catharsis. The team had fought back from a double-digit deficit, forced overtime on Matt Prater’s 50-yard tying field goal, and appeared destined for at least a shot at victory—only to see it stolen in the most controversial fashion imaginable.

As the Bills clean out lockers and turn toward an uncertain offseason, one image lingers: Dawkins staring at his phone, posting those damning screenshots, refusing to let the moment fade without a fight.

The league may not change the result, but thanks to one fed-up left tackle, it had to admit the truth everyone in Buffalo already knew.

The play was dirty.

And everyone had to watch it—again and again.