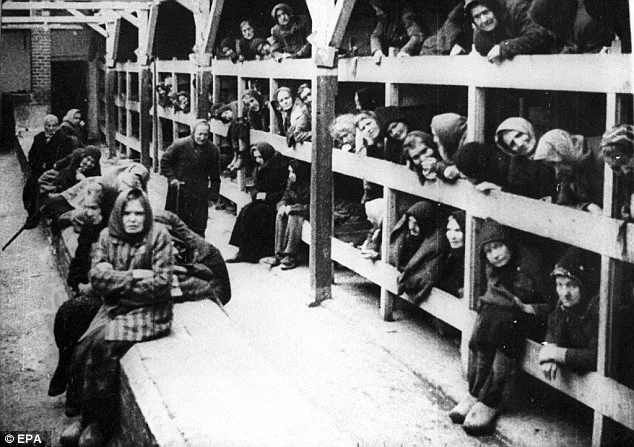

In the shadow of the horror of Auschwitz, a disturbing photograph resurfaces, known as “Smiles of Evil”. Taken in 1944 in Solahütte, a resort of the SS located about thirty kilometers from the camp, this image shows Nazi officers, smiling, relaxing, sharing a moment of camaraderie. Among them, infamous figures like Josef Mengele, Rudolf Höss and Karl Höcker, immortalized in an almost banal scene, far from gas and crematories. This apparent normality is precisely what makes the image so disturbing: how can men responsible for inexpressible atrocities pose with such carelessness?

Karl Höcker’s album, discovered after the war, brings together 116 photographs taken between June 1944 and January 1945. We see SS singing, laughing, or sharing blueberries during an excursion. An image even shows an accordionist leading a 70 -SS choir, some of which directly supervised extermination. A few kilometers away, at the same time, hundreds of thousands of Hungarian Jews were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, sorted at the descent of the trains, and mostly sent directly to the gas chambers. This striking contrast between the lightness of the executioners and the horror inflicted on their victims is unbearable.

This photograph is not a simple snapshot. It reveals a freezing truth about the banality of evil, a concept explored by Hannah Arendt. The SS officers, far from being monsters devoid of humanity, led a social life, had families, and could behave like ordinary individuals. However, they orchestrated an industrial death machine, dehumanizing their victims with terrifying efficiency. The images of Solahütte show a terrifying dissociation: these men could laugh and feast while participating in a genocide.

Höcker’s album, now kept at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, is a rare historical document. He does not directly show crimes, but he exposes the mentality of executioners. The SS sought to normalize their existence, to convince themselves that their actions were part of an administrative routine. This normalization is what makes these clichés so disturbing: they reveal an ability to compartmentalize horror, to separate criminal acts from their daily life.

These photographs confront us with an essential question: how can humanity switch to such barbarism while retaining a facade of normality? They remind us of the importance of vigilance in the face of dehumanization and indifference. By contemplating these “smiles of evil”, we are forced to think about the fragility of human morality and our collective responsibility to never forget. Auschwitz is not only a place or an event; It is an eternal warning against the excesses of ideology and power