During the Second Chinese-Japanese war, the atrocities committed by Japanese forces in China shocked the world, but in Japan, newspapers caused stories of heroism in times of war. A chilling story, reported by theOsaka Mainichi ShimbunIn 1937, he framed a barbaric spree as a sporting event: a “contest to cut 100 people” between two Japanese officers, Tsuyoshi Noda and Toshiaki Mukai. This horrible competition, located in the context of China’s invasion and culminated in the Nanking massacre, reveals the depths of propaganda and brutality in times of war. This analysis deepens the details of the contest, its role in the Japanese media and their lasting controversy, offering an alerting look at a dark moment in history. Share your thoughts: How should we face such atrocities today?

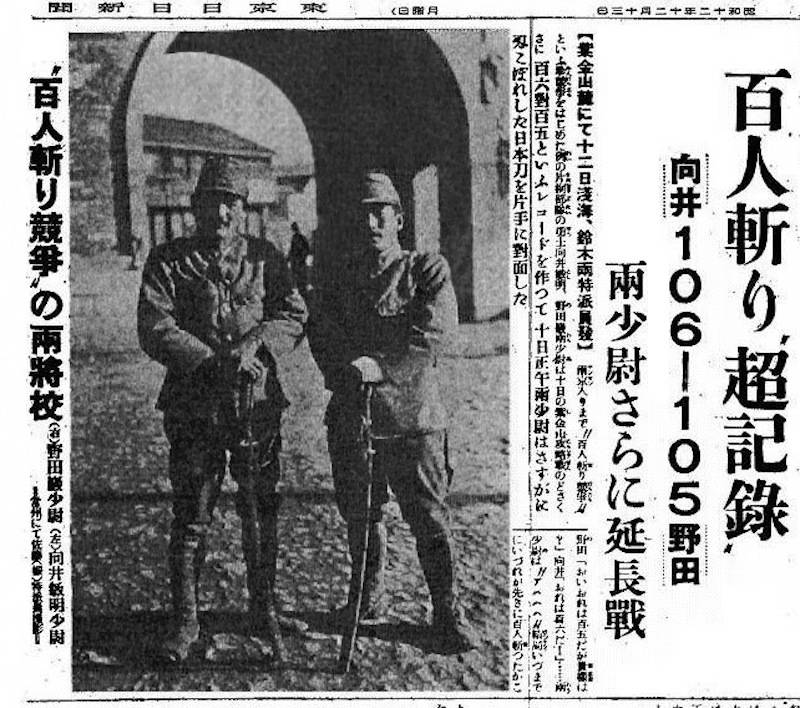

An article that informs about the “contest to reduce 100 people.”

The Second Chinese-Japanese War (1937-1945) was marked by the brutal invasion of China in Japan, which resulted in millions of generalized deaths and atrocities. While the international community condemned violence, Japanese media sought to glorify the actions of their military. The “contest to kill 100 people,” said Fanfarria for theOsaka Mainichi Shimbun, personified this propaganda, turning a horrible killing into a famous show. The career of the Tsuyoshi Noda and Toshiaki Mukai officers to kill 100 Chinese soldiers with their katanas, later revealed that they involve defenseless prisoners, became a symbol of cruelty in times of Japan war, especially during the Nanking massacre. Let’s explore the contest, its interpretation of the media, the gloomy reality and the ongoing debates that surround its legacy.

The origins and frenzy of the contest media

In November 1937, as Japanese forces advanced through China after capturing Shanghai, theOsaka Mainichi ShimbunHe published an article entitled “Contest to kill 100 people using a sword.” The piece detailed a private commitment among the second Tsuyoshi Noda and Toshiaki Mukai to see who could first kill 100 enemy soldiers with their katanas. The newspaper discussed the contest as a sporting event, updating readers in the “scores” of the officers as Danyang advanced from Wuxi. An early report pointed to Noda with 56 murders and Mukai at age 25, with updates such as “The second Lieutenant N broke into an enemy pill … [and] killed four enemies,” and Mukai’s boast, “I will probably cut one hundred for when we arrived in Danyang.” An X Publication of Historyunraveled captured the shock: “Does a newspaper promoting a murder contest? That is propaganda at its darkest point.”

Tsuyoshi Noda y Toshiaki Mukai

Coverage continued with breathless enthusiasm. When the Japanese army arrived in Danyang, the headline declared: “It is 89-78 in the” contest to reduce one hundred, a closed race, what a heroic! “None of the officers had reached 100 murders, but the newspaper framed chosen them as heroic warriors. This narrative firmly contrasted with the reality of their actions, which involved killing defenseless prisoners instead of participating in an honorable combat. The glorification of the media of the contest reflected the Japan War Propaganda Machine as brave heroes.

The nanking massacre: a brutal backdrop

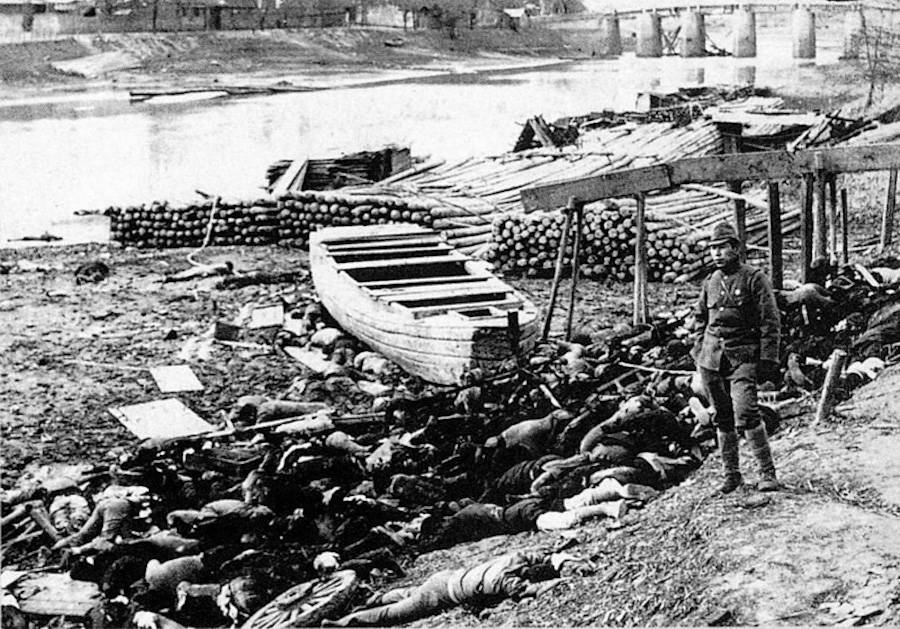

The contest reached its gloomy climax during the Nanking massacre, which began on December 13, 1937, when the Japanese forces captured Nanking, then the capital of China. For six weeks, Japanese troops unleashed an orgy of violence, killing about 300,000 civilians and soldiers, looting and committing generalized violations in what was known as the “rape of puncture.” HeOsaka Mainichi ShimbunThe reporters, ignoring the massacres, focused on the “progress” of Noda and Mukai. At this point, Mukai had killed 106 people and Noda 105, exceeding their initial objective. The officers, unable to determine who first arrived at 100, extended the contest to 150 murders, and Mukai casually pointed out that his sword was “spoiled” for cutting through a helmet. An X position of WarhistoryNow commented: “106 kill, and is concerned about her sword? The insensitivity is chilling.”

The reality behind these numbers was much more ugly. Later, Noda admitted that most of their victims were not armed soldiers but defenseless Chinese prisoners. He described attracting prisoners outside the trenches with false safety promises, only to align and execute them: “We would face an enemy trench … and when we call” ni, laiii! “(You, come on!), The Chinese soldiers were so stupid, they rushed to everyone. Then we would align them and cut them.” This revelation exposed the contest as a grotesque act of cruelty, not a heroic feat, aligning it with the broader atrocities of the Nanking massacre.

Propaganda vs. Reality: the true nature of the contest

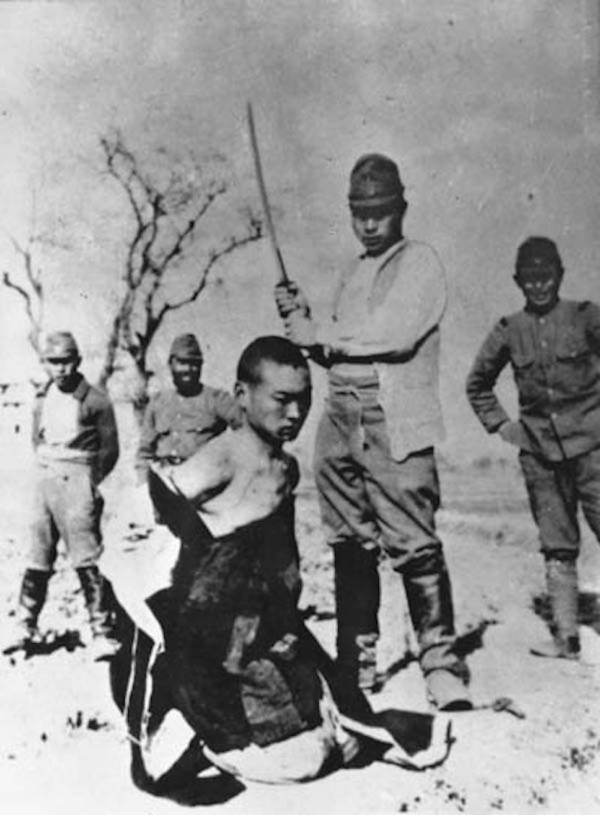

Japanese soldier beheading a Chinese prisoner

HeOsaka Mainichi ShimbunThe painted coverage of Noda and Mukai as frightening gallant who fight against armed enemies, but the truth was much less noble. Most of their victims were prisoners, executed in cold blood, not combatants in hand in hand. Historians have discussed the precision of the contest, and some argue that the numbers were inflated for propaganda purposes. The Noda itself then said that the contest was real, but minimized its scale, which suggests that the newspaper exaggerated the story. However, a 2003 demand for the families of the officers, claiming that the contest was manufactured and damaged its reputation, was dismissed by a Japanese court, which ruled that “the contest occurred and was not manufactured by the media.” An X publication of Truthinhistory said: “The court confirmed that it happened, but Japan’s denialists still retreate.”

This discrepancy highlights the power of propaganda in times of war. The representation of the Japanese media of the contest as a sporting event desensitized the readers of violence, framing it as a patriotic search. This narrative obscured the widest horrors of the Nanking massacre, where massive executions, decapitations and sexual violence were rampant. The contest, while a small part of the atrocities of war became a symbol of how propaganda can distort reality, turning acts of barbarism into glory stories.

Legacy and controversy

The “contest to kill 100 people” remains a controversial issue in relations with Japan-China. After Japan’s defeat in 1945, both Noda and Mukai were tried as war criminals and executed by their roles in Nanking atrocities. However, the broader nanking contest and massacre are still disputed in Japan, and right -wing nationalists often rule out the accounts of civil murders as manufactures. These denials have tensioned diplomatic ties, since China and the international community demand recognition of the atrocities of war. An X post of Asiahistorywatch declared: “Denial of the Nanking massacre ignores evidence as the murder contest: history demands responsibility.”

Bodies stacked by a river during the Nanking massacre.

The legacy of the contest also raises questions about historical memory and responsibility. While the 2003 court ruling affirmed the occurrence of the contest, the debates persist on its scale and context. Some argue that it was a minor episode that emerged, while others see it as emblematic of cruelty in times of war in Japan. HeOsaka Mainichi ShimbunThe role of the amplification of the contest underlines the complicity of the media in the normalization of violence, a lesson that resonates in the current era of erroneous information.

Ethical reflections

The contest forces us to face uncomfortable truths about war and propaganda. When frameting mass murder as competition, the Japanese media dehumanized the victims and glorified violence, contributing to a culture of impunity during the Nanking massacre. This episode challenges us to examine how the media narratives shape the perceptions of conflict and the importance of holding perpetrators. It also underlines the need for historical education to prevent such atrocities from being forgotten or denied.

The “Contest to kill 100 people” is a disturbing reminder of the brutality of the Second Sino-Japanese War and the power of propaganda to mask it. Tsuyoshi Noda and Toshiaki Mukai Killing Spree, held by himOsaka Mainichi ShimbunAs a heroic feat, it was a grotesque act of violence against defenseless prisoners, put against the horrors of the Nanking massacre. His legacy, full of controversy, highlights the importance of facing historical truths and resisting denialism. As we reflect on this dark chapter, we must ask: how can we ensure that such atrocities are never repeated?