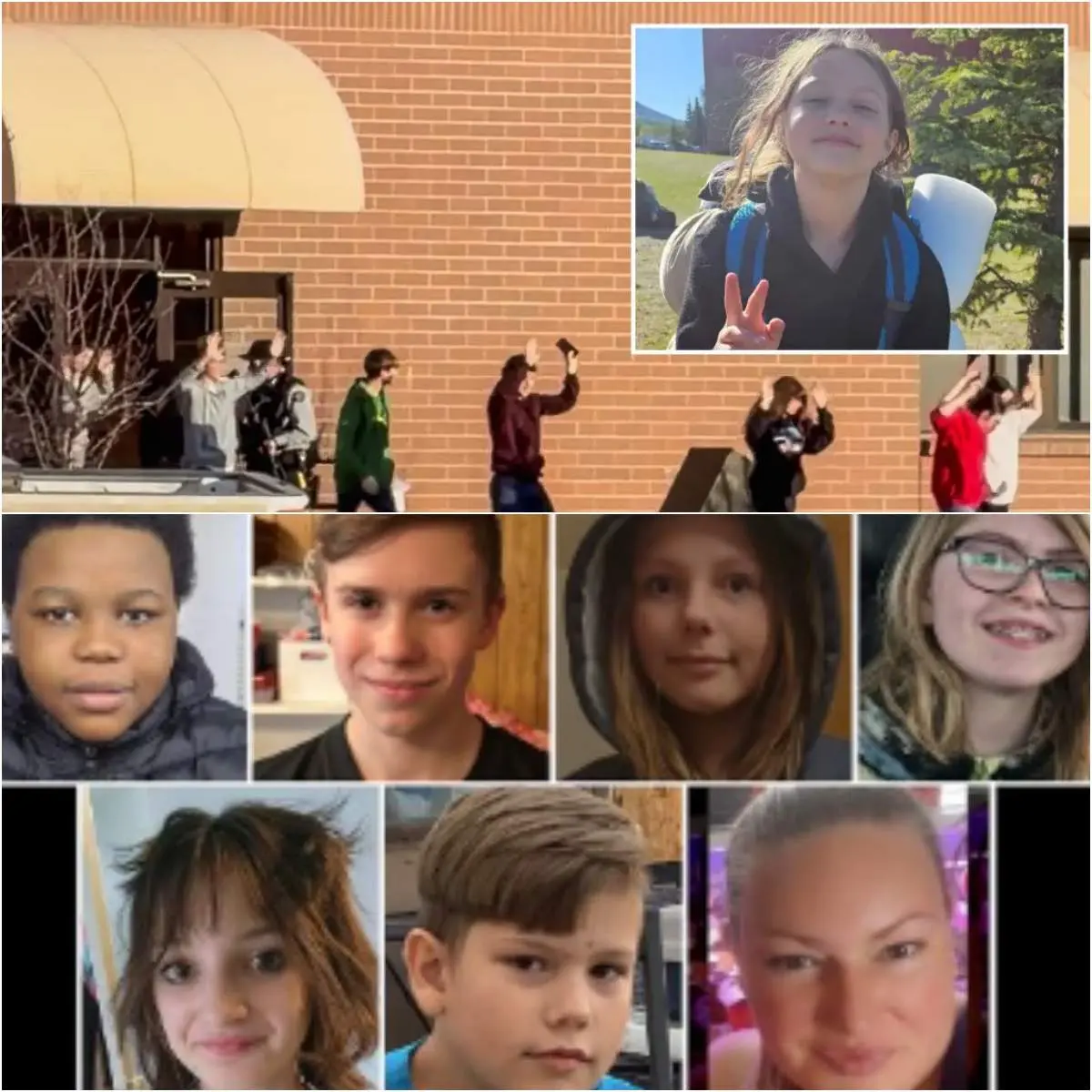

In the shadow of the northern Rockies, where coal dust once defined daily life and the mountains offered a sense of timeless protection, the small town of Tumbler Ridge, British Columbia, continues to grapple with an unimaginable wound. Ten days after the February 10, 2026, mass shooting that claimed eight lives—including five children and one educator at Tumbler Ridge Secondary School—the streets remain hushed, the school building cordoned off, and families face a new, daunting reality: how to help their children feel safe enough to step back into any form of learning.

Parents speak openly now about the invisible scars that linger long after the sirens fell silent. One mother, whose daughter attends the secondary school, described the mornings since the tragedy as heartbreakingly fragile. “They’re scared to walk back through those doors,” she told a local reporter outside the community center, her voice steady but laced with exhaustion. “My girl wakes up crying from nightmares, convinced someone is still in the hallways. She clutches her backpack like it’s armor, hesitates at the front door, and asks if school is really safe.

How do I answer that when I don’t fully believe it myself yet?”

The fear is widespread. Children who once raced to class now freeze at the thought of returning. Some cling to parents longer at drop-off points—if there even is a drop-off anymore—while others withdraw into silence, replaying fragments of what they saw or heard. Nightmares disrupt sleep across households; irritability flares at small triggers; and simple routines—packing lunches, tying shoes—become laden with anxiety. The emotional toll seeps into every corner of family life: dinner conversations turn somber, bedtime stories give way to reassurances, and parents find themselves whispering promises they hope they can keep.

School officials and provincial authorities have responded with urgency. Portable classrooms began arriving this week, lined up like temporary shelters on school grounds, intended to allow learning to resume without forcing students back into the building where the violence unfolded. The British Columbia government has deployed additional crisis counselors, trauma specialists from Vancouver and Prince George, and resources through the Ministry of Education and BC Children’s Hospital. Hotlines like Kids Help Phone (1-800-668-6868) and 310-6789 for mental health support are promoted widely, and community vigils continue to offer collective solace.

Yet many parents question whether these measures—vital as they are—will endure.

A father of three, including two at the secondary level, expressed the growing concern in a community forum: the influx of outside support feels reassuring now, but what happens when the crisis teams pack up and leave? “We’re grateful for the counselors who show up every day, the extra eyes watching our kids,” he said. “But trauma like this doesn’t heal in weeks. My son saw his friends get hurt. He heard things no one should hear. Short-term help is a bandage; we need long-term care, therapists who stay, programs that don’t vanish when the news cycle moves on.”

Experts echo these worries. Trauma specialists emphasize that mass violence shatters a community’s foundational sense of security, particularly for young people whose worlds are still forming. Reactions vary—some children talk incessantly, seeking details; others shut down entirely—but common threads include hypervigilance, sleep disturbances, and a profound fear of ordinary places once taken for granted. Psychologists advise parents to create safe spaces for expression without forcing details, to maintain routines where possible, and to model calm while acknowledging their own fears. “No kid can learn in fear,” noted one advocate familiar with post-shooting recovery.

“Feeling safe has to come before anything academic.”

In Tumbler Ridge, the debate over reopening has taken on added weight. Some families insist they will never send their children back to the original building, no matter the renovations or security upgrades. Others hope portable setups can bridge the gap, offering familiarity without the trauma-laden environment. Student voices, though quieter, reflect the divide: one teen told reporters he misses the routine of seeing friends daily but admits the thought of stepping foot in the school gym—where much of the chaos occurred—makes his stomach turn.

The broader community feels the strain too. Neighbors check in on one another more frequently, sharing meals and childcare. Memorials of flowers, drawings, and candles grow outside the school and community center, many featuring artwork in honor of victims like 12-year-old Kylie Smith, whose vibrant sketches and dreams of art school in Toronto remain vivid in family memories. Parents of surviving children report mixed emotions: relief that their own are alive, guilt over that relief, and a fierce determination to protect what remains.

As portable classrooms stand ready and no firm return date has been set, the town confronts a deeper challenge. Restoring physical access to education is one step; rebuilding trust in safety is another entirely. Parents continue to advocate for sustained mental-health resources—ongoing counseling, school-based therapists, peer support groups, and perhaps even community-wide programs to address collective grief. Provincial leaders have pledged continued assessment and support, but families insist words must translate into lasting presence.

For now, the mountains loom unchanged over Tumbler Ridge, but inside homes and hearts, everything has shifted. Children who once bounded toward school with unburdened joy now pause at thresholds, weighing courage against caution. Parents hold them closer, answer impossible questions as best they can, and cling to hope that time, care, and community will slowly mend what was broken. The most urgent task is no longer about reopening doors, but about helping young hearts believe—truly believe—that ordinary days can return, fragile though they may be.

(Word count: approximately 1510)